The world’s greatest football ground? A photographic centenary celebration of Highbury

Marking the centenary of Arsenal’s move to North London

1. Leaving and Leitch

On 6 September 1913, Woolwich Arsenal made the move that made history. They left behind their Manor Ground in Plumstead, South-East London, and moved into a new stadium in Highbury, North London, in what would four years later become the N5 postal district.

The club moved at the insistence of owner Sir Henry Norris, who had become majority shareholder in 1910. Norris was a divisive figure — a longserving board member at Fulham, he had tried to merge the two clubs before turning his attention to moving his new club north — but there is little doubt that Arsenal, relegated after finishing bottom of the First Division, were drifting towards financial oblivion without the move.

After a friendly FA committee waved away objections to the move, Norris had four months to build a stadium. He raised an impressive £125,000 — around £12.2m at 2013 rates — and spent £20,000 on a 21-year lease of six acres at St John’s College of Divinity. Noted stadium architect Archibald Leitch was enlisted and designed a single stand, the East Stand, with the rest being banked terracing made of compacted earth. Highbury was ready for football.

The image above, from 4 April 1931, clearly shows Leitch’s East Stand, its roof made of nine sections. (Arsenal’s opponents are Chelsea, with their feared Scottish forward Hughie Gallacher aiming to snaffle a rebound.)

2. Three Lions at Highbury

It didn’t take long for England to start playing at Highbury, especially after Arsenal’s controversial 1919 promotion to the First Division. A dozen England matches were held at the Arsenal Stadium (as it was always officially known) between 1920 and 1961.

In this shot from 9 December 1931, Bill “Dixie” Dean moves menacingly toward Ricardo Zamora. The becapped stopper, after whom the Spanish goalkeeper of the year award is still named, wouldn’t back down — in a Spain-England game two years earlier he had played on with a broken breastbone and helped the home side win 4–3, becoming the first team outside the British Isles to beat the English.

No such luck on this occasion at Highbury, now proudly bearing the south-end clock which had been installed in 1930. In front of 55,000 cheering spectators, Spain were beaten 7–1…

3. The Laundry End

By the mid-1920s Norris had the location, the stadium — they bought the site outright in 1925 for £64,000, around £3.3m at 2013 prices — and the First Division place. What they didn’t have was a successful side, but that was about to change.

Rotund Yorkshireman Herbert Chapman had won the FA Cup and two successive First Division titles with Huddersfield when Arsenal hired him in 1925 by doubling his salary. Chapman bought Charlie Buchan and made him captain, and the two concocted a new tactical plan.

The W-M formation was prompted by a change in the offside law: now attackers only needed two, rather than three, opponents between them and the goal-line. Dropping the centre half(-back) from the middle of the field into defence, and the two inside forwards into a more withdrawn role, Arsenal developed a highly effective counter-attacking game.

They came second in 1926, their highest finish yet, but Chapman had a five-year plan and spent time rebuilding the team to his tactics. Bang on schedule, Arsenal won their first major trophy in 1930 — the FA Cup.

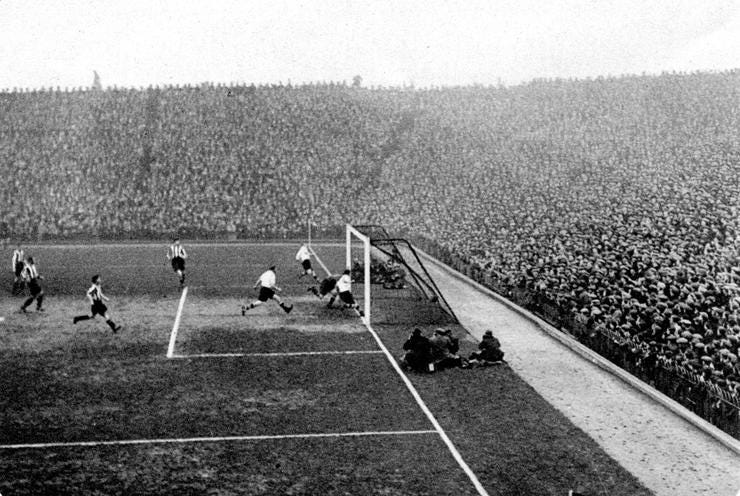

It was the start of a long relationship between club and cup. In this picture from 9 January 1932 — taken looking west along the Laundry End, as the northern terrace was popularly known until the 1960s — a huge crowd had gathered for the Third Round game between Darwen’s so-called £20 team and Arsenal’s, which had cost roughly £50,000. Arsenal won 11–1.

4. Here come the crowds

Good Friday, 14 April 1933: A huge crowd crams into Highbury for the visit of Sheffield Wednesday. After a faltering February of one win in four games (albeit an 8–0 win over Blackburn) and a miserable March of one draw and three losses, Arsenal had seen their lead cut to one point, but had got back on track with a 5–0 win over title rivals Aston Villa and a 4–3 victory at Middlesbrough. The Good Friday crowd would be rewarded with a 4–2 win over Wednesday… and many would come back again the next day for a 2–0 win over Portsmouth which all but guaranteed the title.

By now, the crowds descending on Highbury knew exactly where to go on the Tube, after Chapman had persuaded the London Underground to rename the Gillespie Road station to Arsenal — the only stop on the network to be named after a football team.

Arsenal had followed up their 1930 FA Cup win with the League title in 1931 — the first time they had been champions of England. The following season they had finished second, two points behind Everton, but roared back to take the title in 1933 with a campaign which racked up 118 goals to just 61 conceded — the third lowest that season: it was an era in which defences were certainly were not on top. Hats off to that.

5. Top of the table

Arsenal show off their pots for the 1 December 1934 visit of Wolverhampton Wanderers. Among their possessions that year were the London Combination Cup, the Charity Shield and the Football League trophy, retained by three points with easily the best defensive record in the division.

What makes the second successive title triumph the more remarkable was that Arsenal had lost their innovative, modernising manager Chapman, who in January 1934 had died suddenly of pneumonia, contracted during a scouting trip. He was only 55, but he had changed football forever, forging the role of the modern manager.

Back at Highbury, after the trophy table had been wheeled off, Wolves were dispatched with ruthless efficiency in a 7–0 win, followed up a fortnight later by an 8–0 home victory over Leicester; they won the league for the third successive season with a 115-goal return. No wonder Highbury crowds were booming.

6. Behold the West Stand

Good Friday, 19 April 1935, and Arsenal — well on their way to a third successive league title — are on the attack in an 8–0 win over Middlesbrough. But what’s of interest here is the grand structure in the background.

Arsenal wanted to create for London a stadium to equal or surpass the architectural impressiveness of Villa Park, recognised as England’s finest ground. The West Stand, opened in 1932 at a cost of £45,000 (equivalent to £2.66m in 2013), was designed by Claude Ferrier and William Binnie.

Ferrier and Binnie were advocates of the modish Art Deco movement. In this respect, fortune treated Arsenal kindly. Not all architectural styles date well, but Art Deco has aged gracefully and become seen as symbolic of a hopeful, forward-looking age before the Second World War. Even when it fell out of fashion, it tied in well with Arsenal’s intended image of grandeur and importance.

7. Roof on the Laundry

In 1936, the North Terrace — by now concreted, like the rest of the former compacted-earth standing areas — was given a roof. From under it, the huddled masses could shelter from the weather while they gazed in awe at two matching stands stretching the length of either touchline.

For in the same year, Leitch’s East Stand was torn down and replaced with a new one designed to match the impressive structure opposite it. But whereas the West Stand had cost £45,000, the costs for the East spiralled to £130,000 — equivalent to £7.7m in 2013 — with special attention paid to the quality of the facade.

Here, Arsenal’s Ted Drake attacks the Everton goal on the opening day of the season, August 29, 1936. Despite the presence of Drake, who the previous season had scored seven in one game against Aston Villa and the winner in the FA Cup final, Arsenal would finish in sixth place. The team was ageing, but the stadium was timeless.

8. War wounds

Highbury suffered along with the rest of the country during the Second World War. Like many grounds, it was commandeered for the war effort, becoming an Air Raid Precautions (ARP) station.

And like many buildings in London and elsewhere, it suffered from the Luftwaffe. One night in 1941, the North Terrace roof suffered a direct hit and collapsed onto the scrap that was being stored beneath it, causing a large fire and devastating the terrace.

The southern end — behind which a barrage balloon was tethered — also suffered damage during the Blitz. In October 1940, a 1000lb fell close to the ground and tonnes of concrete were blown over the terraces.

By the time this photograph was taken on 7 October 1949, the North Terrace had been cleared and tidied, but it wouldn’t get its roof back for a while as club and country struggled with the financial consequences of the war.

9. Time added on

The southern end of the ground was originally known as the College End — reasonably enough, given the presence behind it of St John’s College of Divinity, from which the club had bought the Highbury acres. In 1930, Herbert Chapman — inspired by stadiums he’d visited on the continent — had had a 12ft-wide clock installed at the back of the Laundry End terrace. When that got a roof in 1935, the timepiece was moved to the back of the southern terrace, forever after known as the Clock End.

The clock itself had originally counted down from 45 minutes, but the FA didn’t like the idea of undermining the referee’s authority. Arsenal protested but the clock was changed; they did, however, get their own way on the design, rejecting Omega’s tender for the contract because the Swiss manufacturers wanted to include their name on the face.

This picture was taken at the 7 January 1950 FA Cup tie against Sheffield Wednesday. Arsenal went on to win the trophy for the third time, their Cup Final side including renowned cricketer Denis Compton, while opponents Liverpool dropped the man who’d scored in their semi-final against neighbours Everton… a certain Bob Paisley.

10. The outside face of Arsenal

The East Stand, viewed from Avenell Road on 15 August 1950.

The majority of football grounds house their dignitaries in the western stand, to save their grandest guests from squinting into the setting winter sun. However, from the very beginning, Highbury’s heart was on the eastern side — the site of Archibald Leitch’s original main stand.

The new 8,000-seat East Stand had been designed to match the slightly earlier West Stand’s grandeur — but more so, as it was the main entrance and the public face of the club. Inside, it housed previously unheard-of matchday entertainment facilities like a restaurant and cocktail bar.

Outside, underneath a blood-red “ARSENAL STADIUM” and cannon motif, the club placed an omnipresent commissionaire to doff his cap at players and staff. Arsenal were making a statement.

11. Let there be lights

On 19 September 1951, Arsenal entered the floodlit age with a Highbury friendly against Hapoel Tel Aviv.

Two decades before, during a trip to Belgium, Herbert Chapman had become fascinated by the potential of playing under floodlights — no more early kick-offs on winter afternoons and the possibility of midweek evening fixtures, not to mention uniform lighting conditions.

Chapman had lights installed at the training ground, but the FA banned floodlights for competitive senior games. Arsenal were the first top-flight side to play under lights, and by the end of the 1950s floodlights were generally accepted as the future of football.

12. A quick bit of head-tennis

An unusual view of the iconic West Stand — from below, as Arsenal players play football tennis on 8 January 1952 in preparation for their FA Cup match against Norwich.

Arsenal built a half-size training pitch behind the Clock End — it was here that the Second World War barrage balloon was anchored, and here that the 1000lb Luftwaffe bomb had landed. Eventually the club decided to cover the pitch and create a covered sports hall there, although the bare-brick facilities were hardly what the current squad might expect at London Colney.

13. Fog stops play

Even innovative floodlights can’t always help. On 2 January 1954, Arsenal hosted Aston Villa in a League match, but Highbury became enveloped in fog.

Here, Gunners goalkeeper Jack Kelsey peers into the murk, wondering where the next Villa shot will come from. The game was eventually postponed.

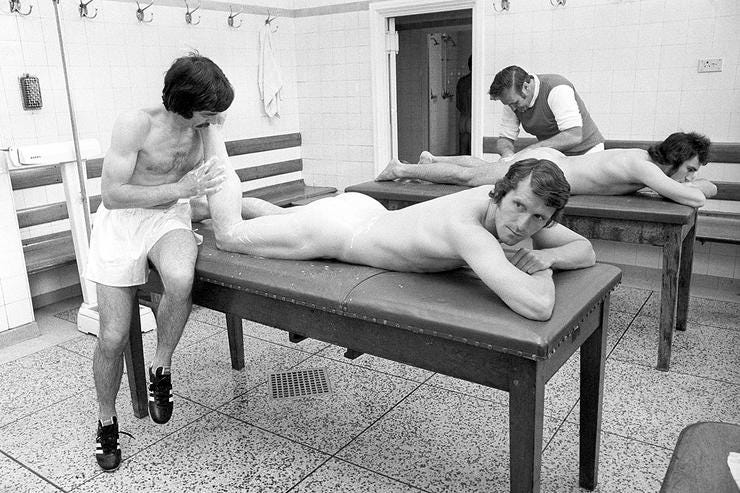

14. Soap foam bath massage, sir?

Now now, behave yourself. Here Arsenal’s Doug Lishman enjoys a soap foam bath message, performed by Les Compton and coach Alf Fields. Fields had signed as a player in 1936, played himself in the film The Arsenal Stadium Mystery, and stuck around at Highbury for decades, eventually retiring in November 1983.

The facilities for players at Highbury were unparalleled in England. As Middlesbrough striker Wilf Mannion noted, “The dressing rooms in the East Stand were beautiful — the marble baths, the under-tile heating. It was pure luxury. You have to remember that this was in an era when a lot of clubs would deliberately leave the heating off in winter, or turned it up high in the summer to unsettle you.

“It said so much for the Arsenal that they provided for your every need. I’ll always remember the white towels laid out for us after games, and even the beer and sandwiches afterwards were of the highest quality. Arsenal had the class to treat all opponents as equals.”

15. Over to Tom at the tactics board

25 April 1955: Arsenal manager Tom Whittaker — in the glasses and white sleeves — talks tactics with his team, all impeccably dressed in two- and three-piece suits.

Note, in the bottom left corner of the picture, the primitive iPad.

16. The corridors of power

Deep inside the heart of Arsenal: The main hall and corridor leading to the offices inside Highbury’s East Stand, pictured on 25 April 1955.

17. Rebel in the marble halls

Arsenal’s new signing George Eastham admires Highbury’s marble entrance hall on 18 November 1960. Actually, the famous marble halls weren’t marble, but terrazzo — but the point was the same.

Eastham is an important figure in football history. In 1959 he had refused to sign a new contract with Newcastle and demanded a move, but the Magpies refused, and furthermore refused to release his registration to anyone else.

This was legal at the time, but Eastham — who was eventually sold to Arsenal after going on strike for months — fought it in the courts; in 1964, a judge ruled partly in his favour, greatly improving players’ freedom to move between clubs.

Eastham, who was a member of England’s World Cup squads in 1962 and 1966 but didn’t play a single minute, later emigrated to South Africa, becoming a vocal opponent of apartheid and coaching local black youth players.

18. Wire in the mud

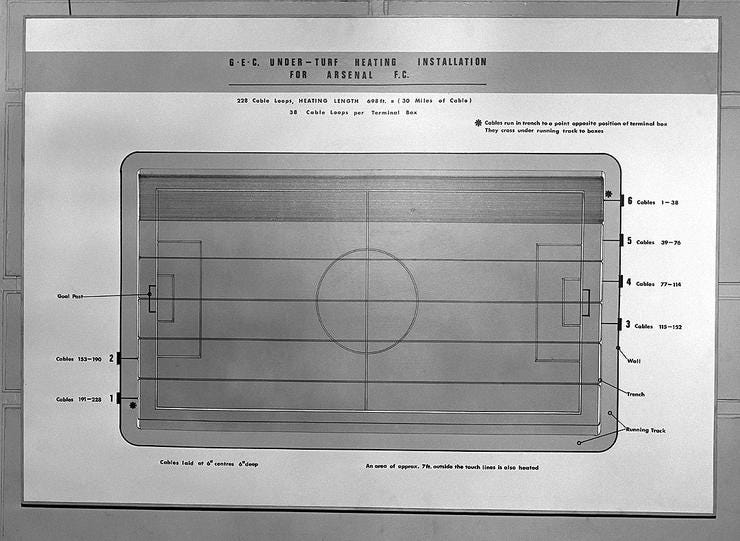

24 April 1964: While Britain goes bonkers with Beatlemania, Arsenal play it sensible by pioneering the use of undersoil (or “under-turf” as the diagram would have it) heating.

Thirty miles of electric cables were laid in trenches six inches under the surface of the pitch — and an area approximately 7ft outside the touchlines, which is good news for keeping the linesman’s toes toasty.

The installation cost Arsenal £10,000 — equivalent to £171,000 in 2013 — but it didn’t last long, as it was replaced in 1970… the years the Beatles split up. Coincidence? We think so.

19. Fight to the finish

On 21 May 1966, Highbury hosted a world heavyweight title fight between Henry Cooper and world champion Muhammad Ali.

Around 40,000 spectators crowded round the ring, erected in the middle of the pitch, to see if Lambeth-born 32-year-old Cooper could stop the 24-year-old champ, but the referee stopped the fight in the sixth round with Cooper suffering a deep gash over his left eye.

Impressed with the facilities in the East Stand, Cooper was moved to comment that “these footballers have got it cushty…”

20. By far the greatest steam…

It’s not quite “we’re gonna need a bigger boat”, but Arsenal certainly upgraded their undersoil heating. Six years after their first attempt at controlling the elements with GEC wires laid six inches under the surface, the club went full steam ahead with an upgraded system.

Instead of newfangled electricity, this one used good old-fashioned steam power, with a large main pipe running the length of the touchline — that’s the one you can see behind the sensibly betrousered workmen, pictured in June 1970 — feeding several smaller pipes running the width of the pitch.

The new system cost £30,000 — the equivalent of almost £400,000 in 2013 — but Arsenal often played on serenely while many other clubs suffered postponements and subsequent fixture backlogs.

Note also in the letters in the north-east corner of the pitch. As at many grounds nationwide, these would display latest scores from around the country; to find out which letter represented which game, you had to buy the programme — or ask someone who already had.

21. Mee time

Into the era of colour TV and decimalisation — and a perhaps unlikely Double.

Bertie Mee had joined Arsenal as physio in 1960, and six years later was elevated to manager. Some saw this as the cheap option, evidence of Arsenal’s waning ambition; but the club had tried the big-name manager — Mee replaced former England legend Billy Wright, whose win percentage was the lowest since before the days of Herbert Chapman — and hadn’t won a trophy since the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

Former Army sergeant Mee instilled discipline, respect and authority befitting of the commissionaire stationed at the East Stand entrance. League Cup finalists in 1968 and 1969, Mee’s Arsenal came from 3–0 down to beat Anderlecht in the two-legged 1970 Fairs Cup final — and a year later became only the second side in the 20th Century to do the Double, winning the league at White Hart Lane before beating Liverpool in the FA Cup Final five days later.

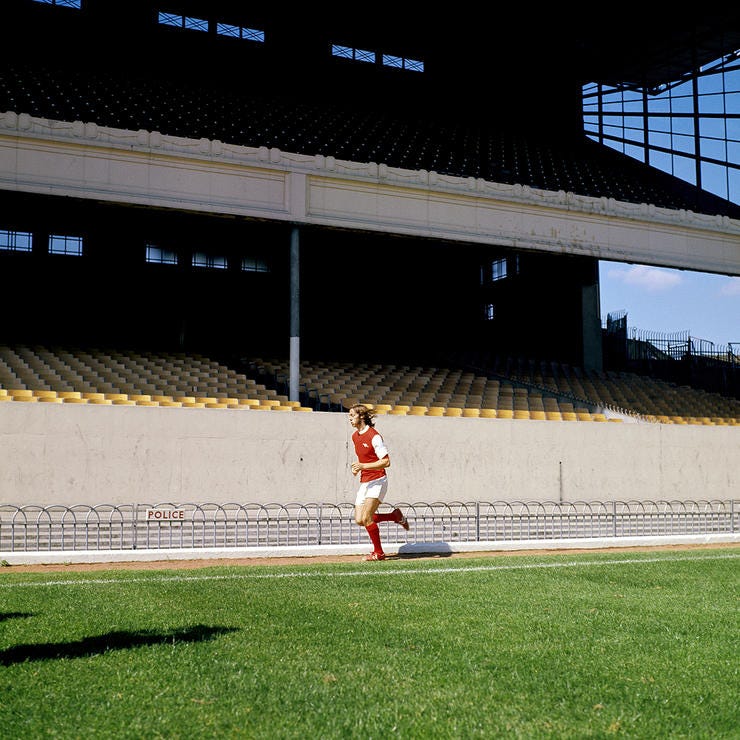

22. Charlie George, superstar

Early August 1972, and Charlie George knuckles down to some pre-season laps of the Highbury pitch. He’s passing the imposing West Stand, which in 1969 had had seating for 5,500 put into its lower deck at a cost of £80,000 — £1.15m adjusted to 2013 prices — while still leaving standing room in front, as was frequently the way in those days.

Islington-born George was a boyhood fan of the club he joined at 15; he made his debut aged 18, on the first day of the 1969–1970 season, and with one of the last kicks of the following season he scored the extra-time winner in the FA Cup Final to give Arsenal the Double. He was still only 20.

An archetypal 1970s maverick, all attitude and flowing locks, George was disciplined twice by the club in 1971/72 — once for headbutting Liverpool’s Kevin Keegan, once for flicking the Vs at Derby supporters after scoring at the Baseball Ground. He later made it up to the Rams — whom he had joined in 1975 after falling out with disciplinarian Bertie Mee — by scoring a hat-trick against Real Madrid in the European Cup.

23. Alone without help

It’s 25 March 1976, and Bertie Mee is high up in the East Stand, surveying his kingdom. While Mee instilled discipline into the team and club, much of their on-field success at the turn of the decade had come from his successful delegation of coaching and tactical duties to Dave Sexton and, from 1968, former Gunners right-back Don Howe.

In summer 1971, tactician Howe left to manage West Brom, and Arsenal were never the same again. Arsenal had finished 5th and 2nd, but then 10th and 16th, and were about to finish 17th. That was enough for Mee to leave, five years after the Double he will always be remembered for.

24. Don, Doyle and Gerry

Another glimpse under the East Stand. The excellent facilities for playing and management staff often led England to pop by, and such was the case in the scorching June of 1976 as the national team prepared to face Finland in a World Cup qualifier.

In the foreground is Man City’s Mike Doyle, while behind him England boss Don Revie — wearing an Arsenal shirt, no doubt to the horror of Leeds fans — personally tends to the massaging needs of captain Gerry Francis.

England beat Finland 4–1, but things didn’t end well. This was the final cap for Francis, despite him being still only 24 and having skippered the side in eight of his 12 appearances after Revie had hurriedly elevated him to the captaincy in favour of the discarded Alan Ball.

Fitness and form kept Francis out of the side for the rest of the decade — by which time Revie had long since controversially walked away from England, who would fail to qualify for Argentina 78. Doyle battled alcoholism and died of liver failure in 2011.

25. A panorama and a puzzle

A minor mystery you may be able to help solve (if so, contact@fourfourtwo.com or @GaryParkinson with #AFC78, please). All we know about this pleasing panorama of Highbury is that it was taken in 1978, directly underneath the Clock End timepiece.

The visitors — not exceedingly well supported, judging by the sparsely-populated seats at the south end of the West Stand — are playing in yellow, but there’s not much evidence of any colours on the terraces except red.

Mind you, in those days it wasn’t always advisable to show your colours at away grounds. On an unrelated note, check out the suedehead stood a few steps in front of the cameraman, his braces round his buttocks (as was sometimes the style) and apparently IAN shaved into the back of his head (as was never the fashion).

26. When Pele needs a little lift…

Two decades before he fronted a 2002 ad campaign for Viagra, Brazilian legend Pele was on hand for a different advertiser: Ingersoll Electronics.

Although Arsenal wouldn’t have a shirt sponsor until the following year (JVC, who lasted until 1999), in 1981 they relented enough to allow the occasional slender strip of advertising on the front of the East Stand, which had been determinedly white for nearly half a century.

On a side note, the nine triangular frontages of Archibald Leitch’s original East Stand had borne the letters A-R-S-E-N-A-L-F-C until Herbert Chapman had ordered them whitewashed out.

Helping Pele achieve elevation are Brian Talbot, Brian McDermott, John Devine, Graham Rix, Kenny Sansom, David O’Leary and Paul Davis.

27. Pitch battles

It wasn’t just advertising that was starting to become a fixture of pitch perimeters during the 1970s and 1980s: at most grounds, metal fencing was erected to keep fans off the pitch — and off each other.

The phrase “football hooliganism” had first appeared in the mid-60s. English football’s first cage had gone up at Old Trafford in 1970/71, and most grounds had followed suit during the course of the subsequent decade, to prevent hooligan fans of rival sides using the pitch as a battle-ground.

Even after the FA decreed cages necessary at venues for the lucrative and prestigious FA Cup Semi-Finals, Arsenal always refused to erect fences, preferring to hope fans respected the sanctity of the grass (and hoping not to further impede sight-lines at the front of the terraces, which were already pretty low compared to the playing surface).

However, fans did sometimes engage in on-pitch battles, such as this 2 May 1981 set-to between Arsenal and Aston Villa fans. Wonder what these two chaps — presumably well into their fifties — are up to now…

28. Paddy and the snowman

You can have all the undersoil heating you want, but if the terraces aren’t safe the game gets called off. As Britain shivered through a terrible winter in December 1981, Arsenal’s game against Middlesbrough was postponed — giving the Highbury groundstaff chance to build a snowman for a photo opportunity.

Pictured are Billy O’Connor, his son Pat, Steve Phillipson and son Wayne, Paddy Galligan and Jimmy Rosie. Galligan in particular was part of the Highbury fixtures and fittings, serving the club from 1974 until they moved home in 2006.

29. Basking on the Bank

A gorgeous sunny August afternoon for the opening day of the 1983/84 season, and they’re cramming them in on the North Bank for the visit of Luton Town. Terry Neill’s side had finished a disappointing 10th the previous season and by December Neill had been sacked.

Neill was replaced by his assistant Don Howe, but the tactician behind Bertie Mee’s trophy successes wasn’t able to bring silverware to Highbury. Howe resigned in March 1986 amid rumours that Arsenal wanted to hire Barcelona boss Terry Venables. Whatever happened to him?

30. Corner kicks

A view from the other end of the North Bank during that 27 August 1983 game against Luton. At many grounds, terraced ends curved round to meet the side of the touchline stands, but few cuddled quite so close to the architecture as Highbury.

Unprotected from the elements and frequently offering restricted views, these areas might have been expected to be unpopular — but lots of regulars loved the unusual angle on the action and close-up view of the stands’ intricate finishings; when the North Bank was later redeveloped without them, there were complaints aplenty.

31. Hanging on

Southampton fans seeking a better view clamber up the corrugated steel at the back of the Clock End. You couldn’t get away with it these days, health and safety, etc.

But seriously, this 1984 FA Cup Semi-Final against Everton was the last to be held at Arsenal for a while due to the club’s refusal to erect perimeter fencing. Five years later, after the horrors of Hillsborough, fences came down across the land and in the 1990s Highbury was awarded two more semi-finals.

32. Millwall aggro

On 9 January 1988, the FA Cup Third Round draw pitted Arsenal against Millwall. Not only were the South Londoners followed by some of the most feared fans in football, but travelling troublemakers had particular reason to be miffed with the Gunners: 18 months earlier, they’d nicked Millwall’s manager.

George Graham wasn’t Arsenal’s first choice to replace Don Howe, who had left in March 1986: besides an interest in Terry Venables, who was busy leading Barcelona to the European Cup final, they approached Alex Ferguson, but the Aberdeen boss was also caretaker-managing Scotland and wanted to wait until after Mexico 86.

Former Arsenal player Graham had taken Millwall from bottom of the old Third Division into the Second (which they would win in 1988 to reach the top flight). Upon his arrival the Gunners had only won one trophy since 1971, but he put that right straight away with the 1987 League Cup.

33. Marching on the league

It’s 17 December 1988, and Manchester United are in town (don’t worry, it’ll fill up in in a bit). Although the visitors are yet to really kickstart their revival — Alex Ferguson’s first trophy is still 18 months away — Arsenal are in the thick of the title race.

George Graham ditched the old guard for a promising crop of youth players, whom he intended to drill to ruthless perfection. They had topped the league earlier in the season but fallen two points behind Norwich; a 2–1 win over United was the first of five straight league victories and Graham’s side would eventually clinch the title in ludicrously dramatic style with an injury-time winner at Anfield. You don’t get that sort of drama every season, kids.

34. Executive decision

The particularly eagle-eyed may have noticed that the previous picture was taken from a new vantage point above the Clock End, which since 1913 had been a simple uncovered terrace, the only development of note in its first 75 years being the addition of a clock and a somewhat ropy camera gantry made out of scaffold.

But in the mid-80s Arsenal tentatively paddled into the waters of stadium redevelopment. Having got planning permission in 1986, the club pondered it carefully then started building work in summer 1988.

The new Clock End stand featured 54 executive boxes in two rows. If it felt somewhat out of keeping with the rest of the stadium, Arsenal fans had it easier than their Spurs rivals, who had seen their beloved Shelf terrace almost completely destroyed by Irving Scholar’s determination to build lucrative executive boxes.

35. Ray of hope

Fans pack the North Bank for Ray Kennedy’s testimonial in April 1991. As a Port Vale apprentice, Kennedy had been told by manager Stanley Matthews that he was too slow to be a footballer and returned to his native Northumberland to work in a sweet factory.

Spotted playing amateur football by Arsenal scouts, he scored a crucial goal in the 1970 Fairs Cup Final and the league winner at White Hart Lane the following season. Arsenal’s top scorer in 1971/72 and 1973/74, he later became a talented attacking midfielder for Liverpool.

Sadly, Kennedy started to suffer from Parkinson’s disease toward the end of his career, and thereafter did what he could to raise money and awareness in the battle against the condition. The Highbury testimonial was a fundraiser — not for Kennedy’s own benefit, but to collect money for medical research.

36. Farewell to terracing

Although 1990’s Taylor Report found the major reason for the Hillsborough Disaster was the failure of police control, it recommended that major stadia be converted to the all-seater model. (Taylor also quoted £6 as a guide price for seated tickets — £11.50 at 2013 prices.)

The Football League stipulated that clubs in the top two divisions should switch by August 1994, and the race was on. The redevelopment of the North Bank — shown here in one of its last games as a terrace — was announced in 1991, by which time Highbury’s capacity had been restricted to 44,397. The record attendance was 73,295 in March 1935 against Sunderland, and Highbury had originally been envisaged as a 90,000-capacity stadium.

37. Sack the board

August 1992, and those supporters are board rigid. Rather than have a blank wall at the north end of the ground during the construction of the new stand, Arsenal commissioned a mural intended to represent their support. But it wasn’t so much AFC as KKK: the mural contained a conspicuous, and hurriedly rectified, lack of non-white faces.

What it did have plenty of was adverts for Arsenal’s new bond scheme. Intended to fund stadium redevelopment, these debentures were announced by a few clubs at the time, creating fervent dislike among fans fearing they were being priced out of the game.

In Arsenal’s case the bonds — priced at £1500 or £1000 — were essentially multi-year season tickets, but incredibly controversial and held as proof that football was trying to reposition itself beyond the reach of its traditional working-class support. Certainly it was a long way from Justice Taylor’s suggested £6 price for a seated ticket.

38. The interregnum

August 1995, and the North Bank stand enters its third season as Highbury enters its interregnum.

Having only won one trophy in 15 years before George Graham’s arrival, the club won six in his eight full seasons. For a time, as Liverpool lost their dominance over English football while Alex Ferguson struggled to turn Manchester United into a fearsome unit, Arsenal were generally recognised at the top flight’s leading team. And with the lifting of the post-Heysel ban on English participation in Europe, the Gunners were setting their sights on the continent.

But the 1994 Cup Winners’ Cup was to be Graham’s last triumph at the club. It emerged that he had received an “unsolicited gift” — a bung, in common parlance — from a Norwegian agent during the transfer of John Jensen and Pal Lydersen. He was sacked in February 1995, and banned for a year by the FA.

Arsenal went for the strait-laced sergeant-major type again in Bruce Rioch, but the Aldershot-born Scotsman turned out to last just one season, 1995/96. During Rioch’s reign the Gunners brought in Dennis Bergkamp; the next manager would make such continental class a matter of course.

39. Old and new

The back of the North Bank Stand, pictured in September 1996. Opened in time for the 1993/94 season, the new stand was designed by the LOBB Partnership and intended to be as sympathetic as possible to the vernacular architecture — hence the flying speed-lines radiating down the side windows, mimicking those on the West and East Stands, and the Thirties-style curved staircases.

Seating 12,400–4,000 upstairs, the rest where the North Bank Terrace used to be — the stand was designed by architect Rod Sheard to be very different from most football grounds, where the space under the stand is simple an area to get through before the game.

“The deep-seated reason,” said Sheard, “is to get people here as early as possible and get them to stay on after. We want to offer services that are at least the equivalent of, if not better than, the local pubs and other amenities.”

40. The view from upstairs

The view from the upper tier of the North Bank Stand, with its immense cantilever roof.

“We’ve tried to break the mould of what stands are meant to look like,” said Rod Sheard, the architect in charge of the North Bank Stand’s construction.

“Most buildings look bulky and robust unless you take care to make them otherwise. We like people to come along and say, ‘What makes that stand up?’”

41. From Japan via the Jumbotron

16 September 1996, and Highbury makes a new friend. Despite his team producing Arsenal’s second-highest win percentage since the 1950s, Bruce Rioch had been sacked in a dispute over transfer funds. If that felt oddly trigger-fingered for the usually cautious club, they quickly replaced him with a man who would make the fans forget all about Rioch.

But first, Arsene Wenger — greeted by one tabloid with the headline “Arsene Who?” — had some contractual stuff to sort out in Japan, so he quickly elevated Highbury lifer Pat Rice from youth-team duties to assistant and caretaker, and addressed his new congregation via the big screens at Highbury.

42. Grounds for celebration

There’s no harm in asking. Lifelong Arsenal fan Steve Braddock, seen here in November 1997, was a groundsman at the Royal Veterinary College. He spied his chance when George Graham was guest of honour at a trophy presentation, and asked if there was a job going. There was, and he got it. That was 1987, and he’s worked for the Gunners ever since.

Although he’s gathered many awards for his work, life at Arsenal started worryingly for Steve, as an awful Highbury pitch was blamed for the Gunners’ troubles. But a total reconstruction in the summer of 1989 worked wonders — the pitch was never relaid again in Highbury’s remaining 17 years.

Braddock, who recalls a young Andy Cole helping him spread fertiliser and Ray Parlour practising on the morning of his driving test by riding a tractor around the Highbury pitch, later switched to the London Colney training ground to bring that up to Arsene Wenger’s exacting standards.

43. Blue sky thinking

There’s not much to say about this photograph, taken on 31 March 2001 before a North London derby with Spurs, except that it’s pretty.

And sometimes that’s enough.

44. Highbury low

4 May 2003, and Highbury is packed and expectant. With the FA Cup final a fortnight away, the reigning Double-holders need a win against their relegation-threatened visitors to keep in touch with Manchester United at the top of the table.

However, things don’t turn out quite as most people expected, as Leeds’ shock 3–2 victory all but loses Arsenal the league title — while keeping the Yorkshiremen in the top flight.

There is a bright side, though: Wenger’s side wouldn’t lose a league game again for 17 months, as the Invincibles reclaimed their league title in impeccable style.

45. Goals, anyone?

Now there’s a scoreline you don’t see every day.

In October 2003, a shadow Arsenal side — including Cesc Fabregas, setting the record for youngest Gunner at just 16 years and 177 days — were 35 seconds from League Cup victory against second-tier Rotherham United when a 90th-minute Darren Byfield equaliser forced extra-time. The next 30 minutes were goalless, but the penalty shootout provided plenty of drama.

Sylvain Wiltord, perhaps the senior Gunner in the scratch side, failed from the spot — but so did John Mullin. Everybody else scored, including Arsenal goalkeeper Graham Stack and his counterpart Gary Montgomery — who had only come on as a sub after Rotherham №1 Mike Pollitt was sent off. Then Stack saved Chris Swailes’ effort and Wiltord tasted redemption by scoring the winner.

A footnote in history, but a fun footnote.

46. The sun sets on Leeds

On 16 April 2004, 11 months after Leeds had come to Highbury and ruined the hosts’ title hopes while saving their Premier League place, they came back and were demolished 5–0. Robert Pires started the rout but Thierry Henry really put the Yorkshiremen to the sword with four goals.

Nine days later, Arsenal made the short trip to White Hart Lane. The 2–2 draw was enough to win the league at the home of their biggest rivals — just as they had in 1971.

Leeds were relegated at the end of the season and have yet to return to the top flight.

47. Turn out the lights

Nearly 55 years after Arsenal had become the first English top-flight side to use floodlights, Highbury’s last night match was suitably climactic: a Champions League semi-final against Villarreal. Kolo Toure’s first-half goal gave the Gunners a slender lead, but that was usually enough: it was their ninth successive clean sheet in Europe’s top competition.

Indeed, a week later in Spain Arsenal made in 10 clean sheets in a row with a 0–0 draw, although they needed a late penalty save from Jens Lehmann to keep it that way. The Gunners became London’s first-ever finalist in Europe’s top club competition, although they would lose the final 2–1 to Barcelona after losing Lehmann to a red card.

48. Squirrel Regis

An interloper on the pitch during the Champions League semi-final against Villarreal.

49. Money can’t buy

For the last ever game at Highbury, against Wigan on 7 May 2006, tickets were understandably hard to come by. Some of the devoted came more in hope than expectation, and grabbed what vantage points they could. Here, three watch through cracks in an East Stand gate.

50. Colossus of Highbury

Thierry Henry didn’t score in his first eight Arsenal games, but he barely stopped thereafter. Arsene Wenger’s £11m investment in the young man he had coached at Monaco initially looked a terrible investment, with even Henry conceding that he had to “be re-taught everything about the art of striking”, but he developed into one of the modern age’s most brilliantly complete forwards.

Henry, pictured here taking a corner in the last game at Highbury, had a particularly special relationship with the old ground. Fittingly, he finished on a hat-trick — to make it 137 goals at the ground — and after completing his treble from the spot, he knelt to kiss the turf. Aww.

51. To Highbury, with love

A floral tribute left by a loving fan after the last game.

52. Just round the corner…

Even as the final game against Wigan was going on (foreground), work continued on Arsenal’s new stadium.

The club had been pondering relocation since 1997, having been denied planning permission to extend Highbury. In early 1998, Arsenal bid for the soon-to-be-redeveloped Wembley, and even staged their next two Champions League campaigns there, but the club withdrew the bid and the site was bought by the FA.

In 2000 Arsenal submitted plans to build a stadium on an industrial and waste disposal area at Ashburton Grove, less than a mile from Highbury.

Shareholders and residents were unhappy but the council were convinced. Construction was delayed while Arsenal raised funds, but selling the naming rights to Emirates helped, and work was completed in July 2006 at a cost of £390m.

53. Protected for the nation

Part of the cost of the new stadium was to be met by redeveloping the old Highbury. With the N5 postcode commanding ever-increasing house prices, it made sense for Arsenal to create residential properties on the old ground — but it would have to be done tastefully.

For a start, the club had to get planning permission for hundreds of new properties in an already densely-populated neighbourhood. But there was also the consideration that parts of the East and West Stands were Grade II-listed protected buildings, and therefore undemolishable: they would have to be incorporated into the new housing.

The West Stand was carefully stripped back to its façade, ready to become the frontage for new apartments being built behind it. Architects Allies and Morrison retained more of the East Stand, including the marble halls, the bronze bust of Herbert Chapman sculpted by Jacob Epstein, and the players’ tunnel.

New buildings were erected in place of the non-listed North Bank and Clock End stands, and the four sides face on to an open space where the pitch used to be.

Highbury Square was opened by Arsene Wenger in 2009. Among its residents is former Highbury favourite Robert Pires.

54. A new domesticity

Although it may have initially seemed an awkward obstacle, the Grade II-listed status of the East and West Stands may have ended up helping Arsenal financially.

Retaining the outward appearance of the old ground maintained an aesthetically acceptable continuity to the neighbouring streets — and indeed as architecture critic Rowan Moore has pointed out, allowed the construction of more apartments in a taller block than the planning department may otherwise have allowed in the relatively low-rise streets of Highbury.

It cost Arsenal £130m to build the 650 apartments of Highbury Square, ranging in price from £250,000 to £1.5m. Housing-market worries after the 2008 global financial crisis caused the club some concern, and 150 properties were sold off to a developer at a 20% discount after some buyers failed to complete their purchases, but Highbury Square cleared its debts to the club by 2010.

Originally published by FourFourTwo on September 6, 2013.