Walking round London pt24: Wimbledon Park to Richmond Bridge

The end of the third quarter: features two large parks, a duelling ground, a former toll bridge and a cheeky ice cream

(ICYMI: The writer is executing a 120km circumnavigation of the capital for charity. These blogs are to publicise the fundraising and consider the vernacular. There’s a full list of chapter/sections at the end of each blog.)

For the past two decades I’ve lived within seven miles of Wimbledon Park and barely even knew it existed, beyond a name on a branch line rarely taken. Such is the density of London and the variety of life.

That branch was opened in 1889 by the London & South Western Railway, linking their line through Wimbledon with the District Railway’s line to Putney Bridge; as was surprisingly often the case, the station caused the suburb rather than the other way round. The station was designed with a flourish typical of the era, namely borrowing bits from wherever appealed: why shouldn’t a semi-Tudor cottage enjoy the odd baroque touch?

Arthur Road, which snakes lazily across the side of the steep easterly slope that defines much of Wimbledon, connected the genteel new houses with the station and beyond it Durnsford Road, running between the dirtier-fingernailed suburbs of Wimbledon and Colliers Wood.

Upon it there’s a suitable superstore from which to acquire a well-earned reward for my daughter and, oh yes, I: a Magnum apiece, and a spare one in the three-pack which has got about five minutes before it melts all over the bag. Way ahead of us up the hill, we spy a couple of familiar figures including the first-time walker who was gritting her teeth and bearing it way back in Streatham, 10km and two and a half hours ago. Surely she’d appreciate it.

There follows five minutes of low-speed thrills, Ella and I quickening the pace to haul in a target now unseen as she disappears round the corner, all the while slurping upon treats rapidly becoming more cream than ice. There’s just about time to take in the impressive houses on Home Park Road before we’re diving into Wimbledon Park itself.

The first thing you see as you survey Wimbledon Park from the handy, if rather ostentatious for purpose, viewing platform is tennis courts by the dozen. In the 16th Century, as part of the grounds of the first Wimbledon Manor House, this place was all about the deer hunting and hawking; now it’s mostly tennis, the reason the world knows Wimbledon’s name.

Indeed, the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club sits across the lake that somewhat surprisingly springs into view after a short climb through an attractive rockery. There’s a children’s party raucously celebrating a birthday on the lake, the juvenile jollity injecting jauntiness to a hot afternoon. They may neither know nor care that the lake was designed by Capability Brown in 1768, and why should they?

By this time Ella and I have hauled in our quarry, handing out a Magnum to a very grateful recipient. The fourth and final ice-cream gets left at the day’s second checkpoint, nestling in the shade on Wimbledon Park. At 17.7km of the day’s 27.7, it’s well over halfway. We leave our new friend enjoying a Magnum and a rest, as we head ever onwards towards Wimbledon Common.

First, some social climbing. The area around the All-England is, frankly, one of London’s nicest and most desirable; it’s also one of the hilliest. As the Capital Ring deviates off Wimbledon Park Road — the line of an ancient footpath between Wandsworth and Wimbledon — and up towards the common, it passes the Competitors’ Practice Courts; many a hopeful rents accommodation around here, hoping to extend into a second week.

The Club is further down Wimbledon Park Road (after its name change to Church Road), but they also own the former Queensmere House, a forbidding E-plan country pile once belonging to Southlands College. Sold to the Club in the 1990s, it overlooks the Competitors’ Courts which we now chug past.

Not everything ages as well as the Queensmere has. Walking up Queensmere Road, opposite the Thursley Gardens end of the social Argyle Estate, there are newishbuild white rendered finish with faux-rock at the bottom and grey metal window-frames; it feels bang up to date for 2010, and that’s about right judging by the weeds on some of the drives. Further up the hill, sub-Huf Haus designs flake gently in the sunshine. And then, atop the hill, Wimbledon Common.

Welcoming the shade of the tree-tunnel, we can see Putney Heath to our right, and it’s well-named: not particularly for Putney, which is a ways down the hill, but very much a heathland. Like the sandy heaths further out in Surrey, it’s all short vegetation, scrubby bushes, young trees, ferns. That’s the view to the north but we’re walking between centuries-old trees. We remind ourselves that there’s “just this and Richmond Park” to go: the final 7k.

Including the contiguous Putney Heath and exclave Putney Lower Common, Wimbledon Common runs to almost 1,200 acres of free land protected for the common man and woman since it was saved from enclosure development in 1871.

The act of protection went against the wishes of the lord of the manor, the 5th Earl Spencer (whose half-brother was Princess Diana’s great-grandfather). He wanted the land enclosed to create a new house and gardens, with part of the land sold off for development. His private parliamentary bill was dismissed by an enquiry and the land passed into public hands.

The Common had already been the site of political battles: it had been a favoured duelling ground, among the protagonists being the serving Prime Minister Pitt the Younger. Two millennia before that it had been an Iron Age hill fort (now misleadingly known as Caesar’s Camp), and it regularly rang to the sound of gunshots until the National Rifle Association left in 1889. Since then it has got a lot more peaceful, the loudest sound usually being the thwack of golf balls.

The Ring’s route across the Common starts with a flurry of activity. It passes the popular windmill, built to an unusual “hollow post” design whereby the main body and all its machinery rotates on a central post, through which a drive shaft takes power to the stones. The mill was built in 1817 to grind corn but is now a museum of milling; in the adjacent cottage, Robert Baden-Powell sat down in 1907 to write Scouting for Boys.

It wouldn’t be the last crossover between the common and popular culture. Besides The Wombles, the common has been a backdrop in War of the Worlds, Doctor Who and Bottom (when Eddie and Richie go camping, presumably with hilarious consequences involving physical comedy).

But for all the popularity, it’s a peaceful place. One of the glorious things about Wimbledon Common is how relatively devoid of humans it is. Once you pass the windmill, its inevitable café and adjoining golf club, and pick your way warily across the fairway and into the woods, you disappear down the hill into a wooded glade which might be miles into the countryside. Once we pass the Queen’s Mere lake, Ella and I walk for fully 10 minutes without encountering a single other person, the only sound being the incessant chatter of birds.

The birdsong accompanies us all the way down the hill, to Beverley Brook (from Beaver-Meadow Stream: the tree-manipulating mammals were common before this was Common) and to the A3, across which we pass from Wimbledon Common to Richmond Park.

Beverley Brook. Beavers not pictured.

Entering through the Robin Hood Gate — not named directly after the highwayman, but a nearby pub which commemorated him — we’re now on London’s largest royal park, which at 2,500 acres is more than double the size of Wimbledon Common and thrice the size of NYC’s Central Park. We’re also leaving behind the SW postcode for TW (Twickenham), the Ring’s first non-London postal locator.

We head up Spanker’s Hill (stop sniggering) and at the car park we stop briefly for the third and final checkpoint. Then we thread between the two Pen Ponds, geographically bang in the middle of Richmond Park. Formerly boggy land drained in 1746, the Pen Ponds — the name probably comes from a nearby deer pen — were once used to rear carp for food, and fishing is still permitted between June and March. Now surrounded by weekend amblers and dog-walkers, we grimace up the long drag of the hill toward the park’s summit, King Henry’s Mound: a possible Neolithic burial barrow later used as a viewpoint, it includes a legally protected vista of St Paul’s Cathedral, 12 miles east.

Pen Ponds

However, just as the hill starts to appear indomitable, the Ring suddenly veers off left to follow the Driftway’s gentle curve through Sidmouth Wood. It emerges near Pembroke Lodge: originally home to the park’s molecatcher, in 1854 it was where the Earl of Aberdeen’s Cabinet decided to proceed with the Crimean War against Russia. More happily, it’s now a popular spot for weddings and ice creams.

Pembroke Lodge

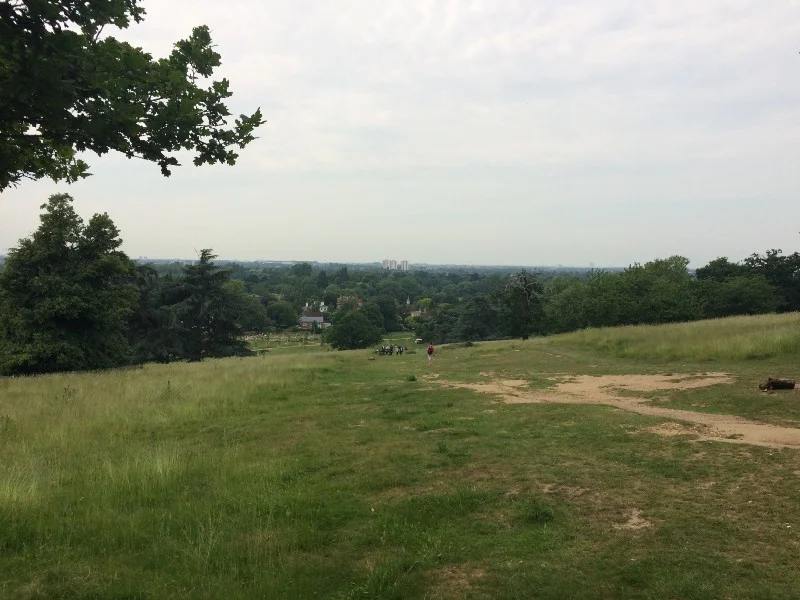

Pembroke Lodge sits atop a steep escarpment, where the underlying London Clay (51 million years old) is topped by the dashing young Black Park Gravel, formed a mere 400,000 years ago by the great Anglian glaciation of the Thames valley. (The gravel is named for an upstream Buckinghamshire area called Black Park, rather than by a bored, sarcastic or uninspired geologist.)

And there is the Thames, snaking serenely along, clearly visible from the Capital Ring for the first time since Woolwich, 55km ago. For those of us who know the area, it’s almost possible to see the riverside finishing line, 3km away in the distance. That lends a certain childlike hop, skip and jump to the rapid descent down the steep western flank of Richmond Park, a topography of tobogganing.

Landing in a heap at the bottom, we’re in Petersham, a potentially pretty little village charmlessly choked by the impatient intrusion of the endless traffic on the A307 from Kingston to Richmond. Nothing new there: 52 years ago, Ian Nairn wrote that “Greater London has some murderous slices of traffic, but this must be one of the most cruel… how the village has stayed intact is a miracle, and a by-pass is essential.”

While his anger is typically earnest and intentions well-placed, I’m not sure quite where Nairn envisaged this by-pass — it would either have to obliterate Richmond Park, the river Thames or the very buildings that make Petersham such a potential delight, “the best place near London to feel the relaxed, sinuous sequence of big 18th-century houses behind walls and trimmed hedges.” There’s a timeless gentility about it, trapped between an ancient park and an ageless river.

Wisely, the Capital Ring flees the main road as soon as possible and throws you round the back of a curious church. Existing since 1206 and possibly back to Saxon times, rebuilt in 1505, St Peter’s was described by Nikolaus Pevsner and Bridget Cherry as being “of uncommon charm”, its innards “well preserved in its pre-Victorian state”. Nairn, typically, is more astringent: “one of those haphazard accretions that the Victorians occasionally overlooked. More odd than attractive.”

I see Nairn’s point, but for me St Peter’s is the better for that oddness, the sense that here is a place that successive generations have seen as important enough to improve while retaining enough respect for the past to avoid flattening it and starting again. Whatever your views on religion, such a place is a route back through the millennia, and it doesn’t always happen like that. Nairn mentions another Petersham church, the impressive red-brick and terracotta basilica of All Saints built in anticipation of a population boom that never came; never consecrated, by 1986 the church had been sold as a private home. Pretty Petersham is a place to pass through, and that’s just what we do.

The Petersham Hotel

Leaving Petersham, we cross Thameside flood meadows, populated by placid cows and overlooked by the florid Italian Gothic of the Petersham Hotel, built 1865. We’re arrowing due north toward Richmond Bridge and the river swings in from the west to join us, busy with pleasure craft, earnestly studied by a photography group.

We pop under the A307 again via a grotto which connects to the Terrace Gardens, climbing graciously up that western slope of Richmond Hill. But we quickly dip back again to the riverside, eager to complete our quarter. The crowds thicken as we near Richmond Bridge, the city’s oldest surviving river crossing.

Under the road and up the hill.

Built from Portland stone in 1774–7, it was accurately described by the contemporary London Magazine as “a simple, yet elegant structure, and, from its happy situation, …one of the most beautiful ornaments of the river”. Two centuries later Nairn called it “The only bridge between London and Marlow to take account of the river as a personality, not an engineering problem. The five graduated arches are partners with the glittering water, and lose no excitement by the gesture.”

Our own excitement is not just in the vernacular but the impending end of our journey. Ella has battled through the discomfort of unpreparedness and enjoyed the day so much that she wants to sign up for next year’s Capital Challenge. For me, there’s still a quarter of this one’s to go — but not until after a nice sit down.

Coming up next: The final quarter

The Mencap Capital Challenge is a charity walk circling London in four quarters, each roughly 30km. You can donate or sponsor the writer at justgiving.com/garyparkinson1974.

NORTHERN QUARTER, SAT 5 MAY 2018

• Pt1: Wembley to East Finchley • Pt2: …to Finsbury Park

• Pt3: …to Clissold Park • Pt4: …to Springfield Park

• Pt5: …to Hackney Wick • Pt6: …to Bow Back River

• Pt7: …to Channelsea River • Pt8: …to Royal Victoria Dock

EASTERN QUARTER, SAT 26 MAY 2018

• Pt9: Victoria Dock to North Woolwich Pier • Pt10: …to Maryon Park

• Pt11: …to Hornfair Park • Pt12: …to Oxleas Wood

• Pt13: …to Eltham Palace • Pt14: …to Grove Park

• Pt15: …to Beckenham Place Park • Pt16: …to Penge

• Pt17: …to Crystal Palace Park • Pt18: …to Upper Norwood

SOUTHERN QUARTER, SAT 9 JUN 2018

• Pt19: Crystal Palace to Beulah Hill • Pt20: …to Streatham Common

• Pt21: …to Tooting Bec • Pt22: …to Wandsworth Common

• Pt23: …to Wimbledon Park • Pt24: …to Richmond Bridge

WESTERN QUARTER, SAT 7 JUL 2018

• Pt25: Richmond Bridge to Isleworth • Pt26: …to Hanwell Locks

• Pt27: …to Horsenden Hill • Pt28: …to Sudbury Hill

• Pt29: …to Wembley, and that's thatl