Walking round London pt27: Hanwell Locks to Horsenden Hill

Featuring a boxer’s biography, an o’ervaulting viaduct, a 17th-century ghost story and a mystery solved

(ICYMI: Having executed a 120km circumnavigation of the capital for charity, the writer has produced these blogs to publicise the fundraising and consider the vernacular. There’s a full list of chapter/sections at the end of each blog.)

Refreshed in mind and spirit from reaching the first of three checkpoints on this final quarter of the 120km capital circumnavigation, we set off up the Grand Union Canal and past the start of Hanwell Locks — a seven-basin chain which is London’s longest set, built in 1794 to take the canal down 53 feet in a third of a mile.

However, we don’t get to see most of this civil engineering marvel as the Capital Ring path cleaves to the River Brent itself, which here splits off from the Union. We follow the shallow river upstream, past a bloke pushing his bike while also reading a sizeable hardback version of Tyson: The Truth. Good to see people reading and riding, if not simultaneously.

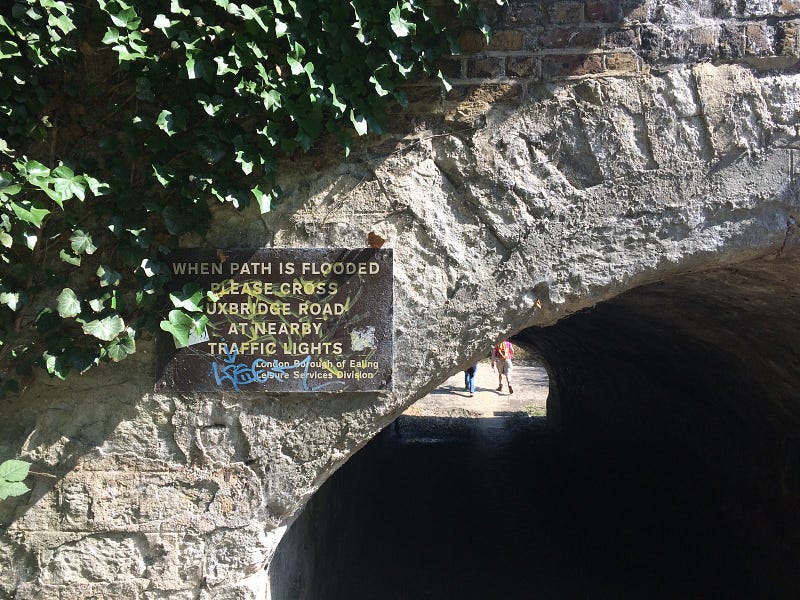

As the weather has been fine for a while, we can take the path through an oft-flooded tunnel under the little old stone bridge which takes the A4020 Uxbridge Road over the Brent and to the Viaduct pub. But the boozer’s not named for this particular viaduct.

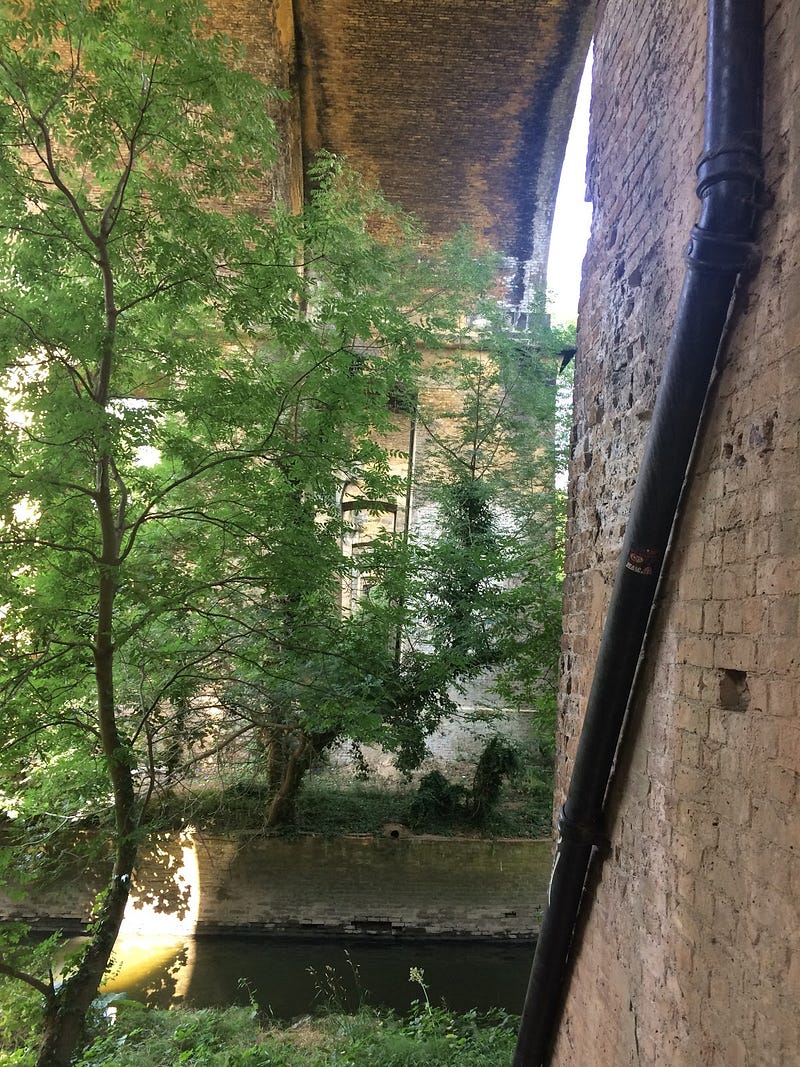

Under the bridge it reeks of stagnant water, but afterwards the view immediately opens up across a field of waving grass to the Wharncliffe Viaduct, admired by many up to and including Nikolaus Pevsner (“Few viaducts have such architectural panache”). It’s all the more impressive for being the first major structural design unveiled by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, then barely 30 years old.

It was built 1836/7 for opening of the Great Western Railway intended to maintain Bristol’s pre-eminence as London’s Atlantic port of choice. That didn’t work out, but the viaduct still carries the Great Western Mainline from Paddington to Bristol.

A brown-brick construction of eight semi-elliptical arches (each spanning 70ft and rising a maximum 81ft from valley floor to parapet), it was the first railway viaduct to be built with hollow piers, which now house a colony of bats.

Pleasingly, thought has continued to go into arrangements around here. From 1839 the viaduct carried the world’s first commercial telegraph, as part of the network alongside the railway line; six years later the telegraph was used to catch a murderer who had caught the 7.42pm from Slough to Paddington. The viaduct later carried the trunk line for the transatlantic cables, and although the line is now electrified, the supporting towers for the necessary wires have been centred on alternate viaduct columns, maintaining a reasonable symmetry.

In case you’re wondering, Lord Wharncliffe — Colonel James Archibald Stuart-Wortley-Mackenzie to his mother — was chairman of the parliamentary committee who pushed the GWR bill through Parliament; his coat of arms is emblazoned on the south side of the viaduct.

Under and the alongside the viaduct, along which trains zoom with a suddenness whose startling nature is not diminished by their regularity, the path winds through the pleasant Churchfields Recreation Ground and well-tended Brent Lodge Park, known to locals as Bunny Park; we don’t see any hopping critters, but there is a goat sanctuary, and bird feeders on trees. Speaking of wildlife, across a tube bridge, we see the first lager drinkers of the day, at 10.20am. There’ll be a lot of that on a scorching hot Saturday with a World Cup quarter-final to come.

The path crosses a golf course — presumably municipal given the dress code is more relaxed than ridiculous — just in time to see somebody slice one worryingly wide off the tee. A sudden instinctive movement brings the first ache in the legs, and once we hit the open spaces of Brent Valley Park the sun climbs inexorably overhead, as it does.

I’m walking with Mike, Dave, Tania and Julia, the latter having come down on the coach from Leeds overnight. We pop out in Greenford on the surprisingly busy Ruislip Road; there’s a debate whether to cut the corner onto Costons Lane but we obediently follow the trail to the crossing. That gives me time to photograph a curious little building now overshadowed by a Lidl and a housing development, wondering what on earth it is, or was.

Later investigation shows it to be a Thames Water pumping station, on the line of the water main from Kempton Park (just over the river from my house) to north London (whence I’m wending my weary way). From 1927 to 1980 north London received 19 million daily gallons of potable water pumped from the works at Kempton via two enormous steam engines, 62ft tall and 800 tons, thought to be the biggest ever built in the UK. They’re both still visitable at the Kempton Steam Museum: one has been restored to working order.

Back up the pipe at Greenford, this smaller sub-station is much more humble but still turned out impeccably, considering its utilitarian intent. It’s still protected: when Lidl applied for planning permission, the German grocers were told the “pumping station should remain unaffected by this development”. And so it sits, squat and prim with its thoughtful two-colour brick coursings and attractive white lintels, but covered in a patina of neglect with its windows boarded up. It wouldn’t cost much to spruce it up. Maybe that should have been part of the planning permission.

For a brief stretch opposite the pumping station the Capital Ring follows Costons Lane, named after a 17th-century landowner called Simon Coston, to whom is attached an interesting local legend. The story goes that there was a windmill in Perivale which had been cursed by a local witch and thus left unattended. A miser occupied the building and went missing; Coston, a young orphan with no friends or relatives, volunteered to go in and investigate — and quickly flew out again, shrieking about a ghost, causing the villagers to scatter…. at which the youngster also disappeared.

Thirty years later, a well-heeled gentleman also called Simon Coston purchased a nearby estate. Locals wondered if the wealthy newcomer was one and the same, and upon his death in 1665 his legal executors revealed that he was. Among his papers was an account of that night, when he had come across the body of the miser surrounded by his money; quickly concocting a plan, he got the jittery locals to disperse then made off with the cash.

Emigrating to Flanders, he became a successful trader before returning home in silent triumph. Trouble is, things didn’t turn out too well for Coston upon his return. His riches diminished, he lost his wife in the great plague of 1665, and took his own life by drowning himself in his own pond.

Maybe that curse still stood, but we don’t stand still. The path through Perivale Park rises mildly but it’s enough to bring on a sweat in the rising temperature. Over the hill (and over a branch of the Brent) into the park proper, and once again we’re treating to the sight of kids playing organised Saturday-morning football, their bright bibs contrasting with the yellowed greensward: it’s been a tough summer for the grass in parched Perivale.

Exiting the park, we’re hit full on by the force of the Western Avenue, six roaring lanes of arterial traffic. It’s a visceral change to the bucolic peace of the walk so far, but it’s another important spoke of London’s radial transport wheel crossed.

Then it’s down through a curious little avenue, a mishmash of styles and about six different houses getting their driveways paved by competing companies obstreperously displaying their pallet-nailed advertising boards. It’s the first domestic street we’ve walked down since Old Isleworth, and it’s not a looker. Nor is the path’s diversion round the perimeter of Northolt RFC, a fenced-in ginnel between rugby club and railway line.

On the apparently apostrophobic Bennetts Avenue we’re overtaken by a Mencap walker — the same one, for the second time. She had passed us on Perivale Park, wordlessly pumping her limbs as she listened to her music, but this time she says hello: she’s in an enormous rush to get home and watch the match with her husband, but had taken the wrong turning. I never see her again, but I hope she got there and enjoyed the game.

Whoever built the semis on Uneeda Drive evidently has a sense of humour to match whoever named it. It’s Tudorbethantastic round here, accidentally postmodern, with most houses proudly displaying their decorative brick and timber arrangements, and a pair further along who’ve gone for the overlapping wood cladding look of a park-keeper’s hut.

After a quick personal detour for a Coke, it’s under the bridges at Greenford station (which still had a wooden escalator in 2014, 27 years after the King’s Cross fire) with its various ages of crossing: the Great Western came in 1904, the Central Line extension in 1947, and the New North Main Line fell to Beeching’s axe in the 1960s.

I observe this alone, as my walking buddies have understandably ploughed on without me. But Julia waits in the shade under a flyover as the Capital Ring passes alongside a McDonald’s, and we fall into easy conversation through Paradise Fields — a former golf course which has been turned back over to nature — while gradually reeling in Tania, Mike and Dave.

By now the path is winding back alongside the Grand Union Canal — this time the Paddington Arm, which snakes into central London as far as Little Venice, where it joins the Regent’s Canal and onwards to Limehouse Basin, which is also fed by the Limehouse Cut from the River Lea we walked alongside all those miles ago.

The five of us make it to today’s halfway checkpoint (16.8km out of 30.5km) at just gone 11.30am, so we’re on schedule for doing a quarter every 1hr 45m. Certainly 11.30am is the halfway point between 8am and 3pm and my co-walkers are celebrating with a longer rest, but I’d rather plough on — my feet aren’t too bad yet, I fear the build-up of lactic acid and of course I have a deadline to hit. For the second half of today’s walk, and thus the rest of the Capital Trail Challenge, I walk alone.

Next: Striding out alone

The Mencap Capital Challenge is a charity walk circling London in four quarters, each roughly 30km. You can donate or sponsor the writer at justgiving.com/garyparkinson1974.

NORTHERN QUARTER, SAT 5 MAY 2018

• Pt1: Wembley to East Finchley • Pt2: …to Finsbury Park

• Pt3: …to Clissold Park • Pt4: …to Springfield Park

• Pt5: …to Hackney Wick • Pt6: …to Bow Back River

• Pt7: …to Channelsea River • Pt8: …to Royal Victoria Dock

EASTERN QUARTER, SAT 26 MAY 2018

• Pt9: Victoria Dock to North Woolwich Pier • Pt10: …to Maryon Park

• Pt11: …to Hornfair Park • Pt12: …to Oxleas Wood

• Pt13: …to Eltham Palace • Pt14: …to Grove Park

• Pt15: …to Beckenham Place Park • Pt16: …to Penge

• Pt17: …to Crystal Palace Park • Pt18: …to Upper Norwood

SOUTHERN QUARTER, SAT 9 JUN 2018

• Pt19: Crystal Palace to Beulah Hill • Pt20: …to Streatham Common

• Pt21: …to Tooting Bec • Pt22: …to Wandsworth Common

• Pt23: …to Wimbledon Park • Pt24: …to Richmond Bridge

WESTERN QUARTER, SAT 7 JUL 2018

• Pt25: Richmond Bridge to Isleworth • Pt26: …to Hanwell Locks

• Pt27: …to Horsenden Hill • Pt28: …to Sudbury Hill

• Pt29: …to Wembley, and that's that